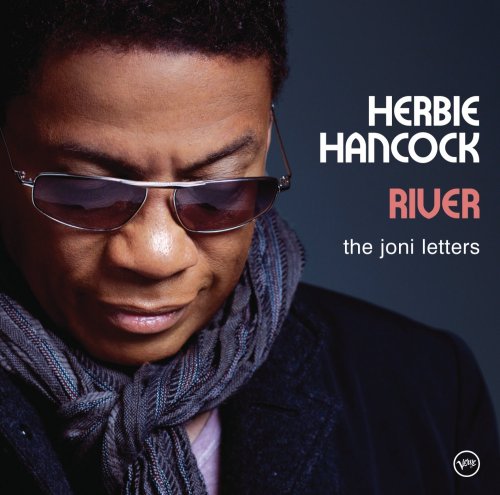

herbie hancock's 'river'/ ry cooder's 'i, flathead'

i rarely write about music here, partly because i don't feel qualified to do so, and mostly because i struggle to capture the meaning of sounds in words, but i've been so touched by two new(ish) albums over the past fornight that i had to mention them. herbie hancock's 'river' - a love letter to joni mitchell from the jazz pianist whose playing can be evoked but not circumscribed by images of eating chocolate, or lying in a hot salt spa, of breathing deeply on a balcony balmy night, or maybe just the words 'it's bloody amazing', and ry cooder's 'i, flathead' - an acclamation of youthful days when the most exciting thing in the world was driving a cool car and trying to get a cute girl to catch your eye ... hancock's music drove me home last night; cooder's made me think. i'm going to stop writing and listen to corinne bailey rae sing 'river', and leave you with the thought for the day i wrote for radio ulster last week.

"You know when you hear a wonderful piece of music for the first time, and it captures your attention so much that you just have to hear it again straight away? Last week it happened to me when I heard a new song by Ry Cooder, the slide guitarist and facilitator of the amazing band of elderly Cubans, the Buena Vista Social Club. Cooder has a new album out with the impossibly brilliant title ‘I, Flathead’, an older man’s love songs to the feeling of being young, and learning the romance of driving a really cool car.

The album is about the exuberant exhiliration of living completely free, which a friend of mine likes to describe as dancing like no-one’s watching. When you apply this idea to the rest of life – to the choices we make every day, from what to eat to what route to take to work, to who to live with, and what to do with the years we have on earth, it’s a useful corrective to the monotonous patterns many of us seem stuck in.

Research shows that when you ask elderly people about their regrets, they tend to agree that if they had it over again, they would take more risks. They might choose a different career path with less financial security because it would be more psychologically rewarding. They might take the trip they always avoided because they didn’t speak the local language. They might, as Shakespeare has Edgar say in ‘King Lear’, ‘speak what we feel, not what we ought to say’.

What would it mean to follow this advice, and ‘dance like no-one’s watching’? Some of us today need to be reminded that no matter what the circumstances of our lives, what has happened to us, or how we have fallen short of our own ambitions or values, we still have freedom to choose to get back in the game. We can take the risk we’ve always avoided. Today might be the day that someone listening picks up the phone and calls an old lover, who turns out to have been waiting for years to hear from them; or someone else quits the job that deadens their soul, and pursues the creative dream that has lain dormant since they were a teenager; or someone else decides to stop allowing the pain of past trauma to prevent them living a life where the only limit is their own vision of the possible.

Today, someone’s going to dance like no-one’s watching, someone’s going to speak what they feel, not what they ought to say, someone’s going to get back in the game – it doesn’t matter which metaphor you use: but if today is a day for someone to free themselves from whatever unnecessary restrictions they have allowed to hold them back, why shouldn’t that someone be you?"