Further Thoughts on Non-Violence (3): How can we talk about Forgiveness?

Ok, so the photo above might seem a bit obvious, but two things are also self-evident to me. 1: Parts of the place where I grew up really are that beautiful. 2: A re-engagement with beauty is perhaps the core of what is necessary to save the world.

I'm back home in Belfast briefly, for the first time since I moved to the US. It's beautiful to be re-welcomed by longstanding friends, but there is still a kind of detachment in knowing that I don't live here anymore. I'm back at a time when tragedy has made its presence felt with force, in the midst of the long and difficult road toward a peaceful political settlement.

Three people were murdered, and several have been injured in the past few weeks, in attacks carried out by people who do not support the process that has already led to a power-sharing government, the release of all politically-motivated prisoners, and the establishment of a strong human rights and equality culture, along with one of the most transparent policing services in the world. After nearly 4000 people were killed, most between 1969 and 1994, three new names were added to the list read out on Good Friday at a memorial service. 48 year old police constable Stephen Carroll and young soldiers Patrick Azimkar and Mark Quinsey were shot dead in March.

On the way from the airport when I arrived back a few days ago, I drove past the barracks where the soldiers were killed; I hadn't felt those emotions for a long time. There is a changed atmosphere for some of us. We have had traumatic memories re-stirred; the old feelings of cautiousness with strangers, and discretion about personal conversation are detectable, and could threaten to return to everyday life in northern Ireland. At the same time, some of the reaction to the murders has exemplified how far we have come as a society, with cross-community condemnation mingled among profound public mourning, and some large scale protests by people sick and tired of being used as human shields for ideological purity.

It's impossible to be sure of what it would take to prevent further violence. The people arrested in connection with the killings range from 17 years old to middle age. As far as they are concerned, their political cause legitimises the use of violence to achieve what they perceive to be justice. Confronting them with the human costs might make a contribution to challenging this notion, which, to my mind, has never been legitimate. But we struggle, because our public conversation these days seems so colonised by cynicism and shortcut that a re-assertion of human dignity may be not only necessary, but inevitable, as people are confronted by the costs of not taking life seriously.

There's a specific example I have in mind. I'll write more about it later. For the time being, it's Easter Sunday, and the resurrection that hundreds of millions are remembering offers the most transcendent reason to value human life: because it might just last forever.

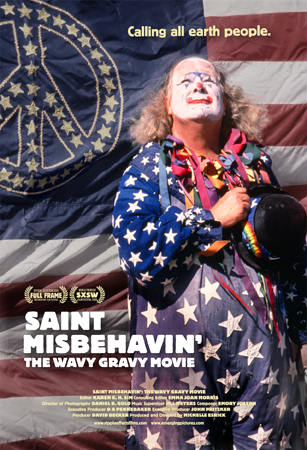

I don't usually do recommendations of the week; heck often I don't do recommendations at all. But after the exhiliration of wall to wall documentary at the Full Frame Festival, I settled in last night, as I am wont to do, to catch up on a film I know I should have seen earlier, but was watching something else at the time.

I don't usually do recommendations of the week; heck often I don't do recommendations at all. But after the exhiliration of wall to wall documentary at the Full Frame Festival, I settled in last night, as I am wont to do, to catch up on a film I know I should have seen earlier, but was watching something else at the time.

I'm currently writing a book about how cinema explains my adopted country - the most well known art form of the US should reasonably be expected to be a key interpretative tool for understanding America, right?

I'm currently writing a book about how cinema explains my adopted country - the most well known art form of the US should reasonably be expected to be a key interpretative tool for understanding America, right?

My friend David Dark has a new book out. It's called 'The Sacredness of Questioning'. It's a philosophical-theological-psychological-communitarianistical-nashvillianestical-cinematical-musical thrill ride. It mentions the Coen Brothers, Flannery O'Connor, Tom Waits, and the mysterious figure who lives in the basement known as Uncle Ben.

My friend David Dark has a new book out. It's called 'The Sacredness of Questioning'. It's a philosophical-theological-psychological-communitarianistical-nashvillianestical-cinematical-musical thrill ride. It mentions the Coen Brothers, Flannery O'Connor, Tom Waits, and the mysterious figure who lives in the basement known as Uncle Ben.