'Sita Sings the Blues: Art Should Be Free, but Artists Need to Eat

The film with this image as one of its centerpieces is currently available to watch for free at Reel 13.

The film with this image as one of its centerpieces is currently available to watch for free at Reel 13.

I'll say it again.

The film with this image as one of its centerpieces is available to watch for free at Reel 13.

The creator (director, writer, animator, editor, pretty much everything else-er), Nina Paley is some kind of genius.

To fuse ancient Hindu literature with postmodern New York relational angst, mingled with 1920s sultry blues and contemporary competing narration from delightful (and delighted) semi-experts makes 'Sita Sings the Blues' the most imaginative film I've seen this year.

The fact that Paley has made it available through a creative commons license (partly due to the copyright labyrinth) not only speaks volumes about her generous nature (it shines through in the light touch of her movie) and the future of film distribution, but makes 'Sita' probably the most fully realised cinematic incarnation yet of the paradox the poet and cultural critic Lewis Hyde is getting at in his book 'The Gift'. Art should be free, if it is to be faithful to the place from which creative urges come; but artists need to eat.

That paradox is at the heart of how market economies diminish the quality aesthetic. (Best current example: A friend tells me that the version of 'Wolverine' he downloaded is far better without industrial special effects than the one that will be released to cinemas ever could be: for the spectacular explosions that are the reason for its absurdly high budget only serve to diminish the human/hybrid story.) Even this blog exists at the axis of this paradox - writers need to make a living as well as making a life - but, to reflect on only the part of my work that is film criticism, the potential for economic bonding among cinema's impoverished professional fans has never been greater. Nor the potential for envy toward those who actually get paid for their work.

'Sita Sings the Blues', therefore, is one of the most inspirational works of art we could see right now. Nina Paley has given us a gift, a beautiful, smart, often hilarious film that we can watch for free. Forever. It's free, but I'm going to send her a donation, because I have consumed her gift, and I want her to be able to make more films. I'll write to her after posting this, and maybe she'll write back; and a community will come into being, maybe just for the duration of one email and its reply. But I'll have had a direct relationship with the person who made this film and deserves my thanks - not just for the work of art itself, but for her risky decision to be in the vanguard of a new movement that can only be good for the world.

And whether or not you buy my logic, please do yourself a favour and see this wonderful film 'Sita Sings the Blues'. Its director couldn't have made it easier if she came over to your house and showed it herself.

You’ve seen Eddie Adams’ photographs before. You’ve turned away from the one that made him famous; that of General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Vietcong prisoner, an image that some people credit with creating a turning point in the Vietnam War. Woody Allen covered a wall with the photo as a way of satirizing the tendency of some artists to wallow in self-pity while the world burns; at least one musician used it as home décor to remind – he says – himself of the tortuous nature of how other people live.

You’ve seen Eddie Adams’ photographs before. You’ve turned away from the one that made him famous; that of General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Vietcong prisoner, an image that some people credit with creating a turning point in the Vietnam War. Woody Allen covered a wall with the photo as a way of satirizing the tendency of some artists to wallow in self-pity while the world burns; at least one musician used it as home décor to remind – he says – himself of the tortuous nature of how other people live.

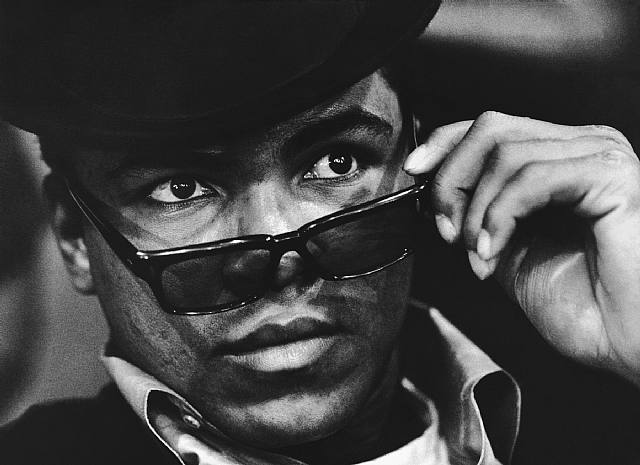

The best known African singer in the world, the most significant cultural figure in Senegal, the voice that 'Rolling Stone' described as perhaps containing the whole of the continent (though I'm not sure whether that's a kind of silly post-colonial statement or a magnificent expression of what it can do), father, son, brother, political activist, mystic, and frankly one of the most obviously attractive human beings I've ever seen, Youssou N'Dour is the subject of a new documentary by Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, 'I Bring What I Love', which I saw last night at the Nashville Film Festival.

The best known African singer in the world, the most significant cultural figure in Senegal, the voice that 'Rolling Stone' described as perhaps containing the whole of the continent (though I'm not sure whether that's a kind of silly post-colonial statement or a magnificent expression of what it can do), father, son, brother, political activist, mystic, and frankly one of the most obviously attractive human beings I've ever seen, Youssou N'Dour is the subject of a new documentary by Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, 'I Bring What I Love', which I saw last night at the Nashville Film Festival. My friend Dave Dark's wonderful new book 'The Sacredness of Questioning Everything' hasn't yet been given to President Obama by Hugo Chavez, at least as far as I know, but I'm sure that's only because the Spanish translation hasn't been published yet...You can, however,

My friend Dave Dark's wonderful new book 'The Sacredness of Questioning Everything' hasn't yet been given to President Obama by Hugo Chavez, at least as far as I know, but I'm sure that's only because the Spanish translation hasn't been published yet...You can, however,