The Violence of Criticism/The Criticism of Violence

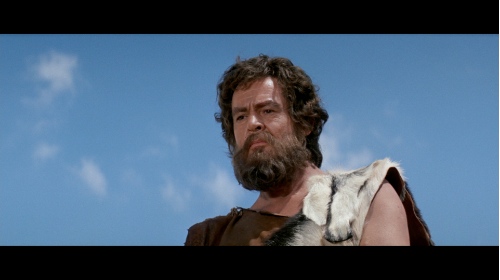

An Original Critic - John the Baptist in 'King of Kings'

I'm watching Nicholas Ray's 'King of Kings', probably the most political of classic/epic Jesus biopics (which to my mind makes it the most interesting - if Jesus isn't engaged with real power in the world as we experience it, then what's the point?), and Jeffrey Hunter's blue-eyed Messiah has just told the assembled mob of intended stoners to cast rocks only if they themselves 'have no sin'. Along with being the most profound elucidation of why killing people as punishment is wrong, maybe it's also the easiest way for me to describe the lens through which I view cinema (more on this here). Too forgiving, some say. Perhaps. But I'm fairly convinced that snark is one of the wastes of our age, that negative copy is the easiest to write (because it's the easiest to think), and that a work of art should be judged at least partly on terms relative to what it's attempting to do (our experience of 'Transformers' isn't going to be most richly served by comparing it to 'Aguirre, Wrath of God').

I guess my hermeneutical mode for film criticism falls somewhere between Ebert's relativism and others' absolutism, in that I think works of cinema should be judged both on their merits relative to factors such as their genre, the intent of their authors, the resources available to their production and the meaning of these works in the world. Given that my particular prejudices lead me to assert that the role of storytelling in shaping what it means to us to be human, and that the story of the myth of redemptive violence is the foundational story of our culture, and that therefore we need to find and tell stories that transcend our addiction to the fight or flight dichotomy, then I also assert that narrative fictions should be judged according to their posture moving toward or away from such transcending.

In other words, my theory of art is simple: 'craft' isn't just technical, it's moral; of chief importance in the world we inhabit is the universal call to flesh out peace, love, and the family of humankind. You might judge that sentimental, but only because the concepts have been diminished by the superficial way our culture talks about them. When peace, love, and the family of humankind are actually actively embodied, this looks rather less like sentimentality, and more like the kind of force that might prevent the next Hiroshima or 9/11 or Sarajevo or My Lai. If that's sentimentality, I'll take a double portion.

This matters for storytellers and those who work to interpret stories told by others because the very possibility of peace is repressed or released by the narratives to which we pay allegiance; movies contain some of the most powerful embodiments of the stories human beings tell about ourselves. Life's too short - and, at times, too threatened - to avoid a moral/transcendent analysis of cinema because it's become chic to seem aloof, hyper-tolerant, or more-liberal-(or conservative)-than-thou. That avoidance is impossible anyway - better to stop pretending that we can even achieve it, name our prejudices as best we can, and see our work as critics to be just another part of the story the human race is telling itself about itself. In responding to the typical narratives of our culture, which are so often ultimately structured by and for violence, critics can participate in or challenge the violence of those stories. We're not just responding to the representation or transcending of the myth of redemptive violence; it's a high calling - because we're either representing or transcending it in and by our own work.