Some Thoughts from the New Book: What is America?

I'm currently writing a book about how cinema explains my adopted country - the most well known art form of the US should reasonably be expected to be a key interpretative tool for understanding America, right?

I'm currently writing a book about how cinema explains my adopted country - the most well known art form of the US should reasonably be expected to be a key interpretative tool for understanding America, right?

I don't want to give too much away at this point, but suffice to say, Oklahomans know how to dance, Massachussetts residents like sea food, and people from Illinois believe in any means necessary to stop other people drinking whiskey.

What's most obvious from my research so far is that America (and I use the term 'America' in the knowledge that I'm referring to the 48 contiguous states between Mexico and Canada, the large cold one to the left, and the exotic series of islands on the way to New Zealand. I usually say 'the United States', but 'America' has become such a mythical term that it seems appropriate) hasn't settled its own mind about what it wants to be.

Kansas produced a militaristic President (Eisenhower) who later said that no glory in battle was worth the blood it costs.

Oklahoma - one of the most conservative states in the Union - also has the most registered Democrats.

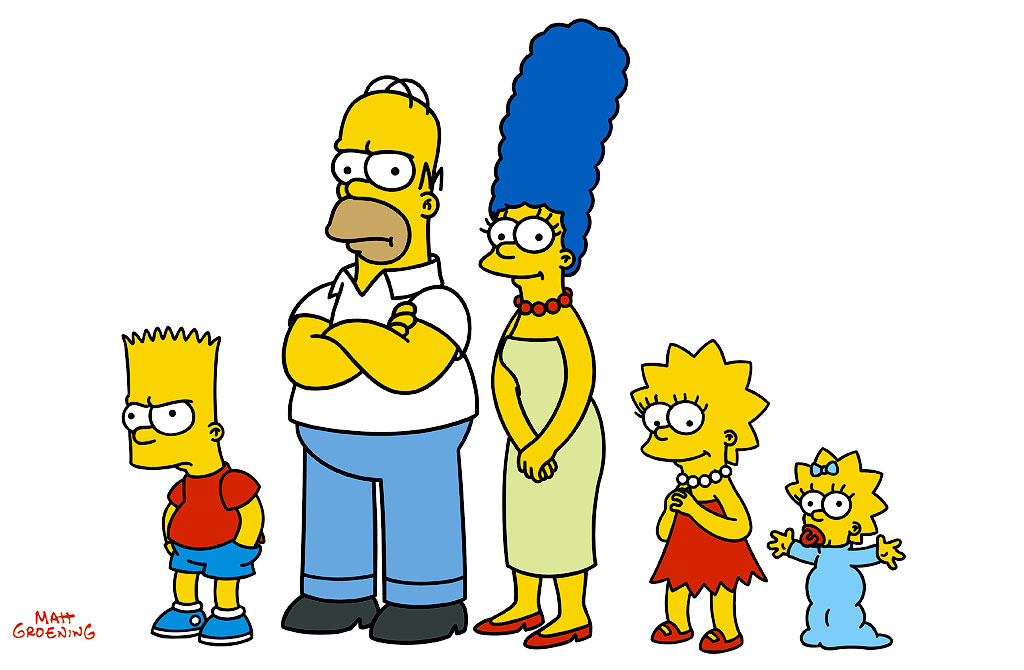

The popular movies produced in the land that loves to call itself 'free' are disproportionately pre-occupied with the violent taking of human life for our viewing pleasure.

America, in the movies, at least, is the definition of paradox. And its mind is not yet made up. Zhou Enlai is supposed to have said, in the 1950s, that it was 'too early to tell' the consequences of the French Revolution of 1789 - and that social movement was only thirteen years younger than newly constitutionalised America. So then it's also too early to tell what America is. Or maybe I'm misleading myself - for diversity of opinion does not necessarily equate to a lack of confidence in national ideals. Maybe that's what America is: everything?

So, friends, I'd value any thoughts on the following question, in the comments section below:

What, in one sentence, is America?

My friend David Dark has a new book out. It's called 'The Sacredness of Questioning'. It's a philosophical-theological-psychological-communitarianistical-nashvillianestical-cinematical-musical thrill ride. It mentions the Coen Brothers, Flannery O'Connor, Tom Waits, and the mysterious figure who lives in the basement known as Uncle Ben.

My friend David Dark has a new book out. It's called 'The Sacredness of Questioning'. It's a philosophical-theological-psychological-communitarianistical-nashvillianestical-cinematical-musical thrill ride. It mentions the Coen Brothers, Flannery O'Connor, Tom Waits, and the mysterious figure who lives in the basement known as Uncle Ben.

I am a European, and therefore an inheritor of a tradition that includes both life-enhancing, humanising political dissent (Mennonites and Amish, the Reformation, the anti-slavery movement) and racist, destructive control (conquests both political and economic, slavery, genocide). I am a European, and so, even though I was not born when it happened, the

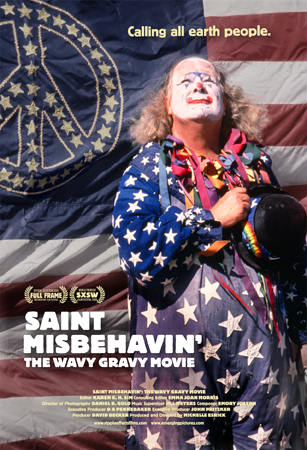

I am a European, and therefore an inheritor of a tradition that includes both life-enhancing, humanising political dissent (Mennonites and Amish, the Reformation, the anti-slavery movement) and racist, destructive control (conquests both political and economic, slavery, genocide). I am a European, and so, even though I was not born when it happened, the  Let's face it, some of us who hope to be inheritors of the peace activist tradition are regrettably notable for often lacking public credibility. While we all know people working at a grass roots level who can be held up as examples of the most heroic kind, often the public face of peace activism appears either ‘wooly’ or ‘strange’. In the UK, for instance, the de facto leader of the anti-Iraq War movement was an arrogant politician with a questionable ethical record, and without a meaningful strategy for addressing conflict.

Let's face it, some of us who hope to be inheritors of the peace activist tradition are regrettably notable for often lacking public credibility. While we all know people working at a grass roots level who can be held up as examples of the most heroic kind, often the public face of peace activism appears either ‘wooly’ or ‘strange’. In the UK, for instance, the de facto leader of the anti-Iraq War movement was an arrogant politician with a questionable ethical record, and without a meaningful strategy for addressing conflict.